Monumental Last Supper and melting watches

Dalí, flamboyant and controversial, considered himself to be a genius. Others might have believed him to be a lunatic. But his outrageous and masterfully rendered paintings that often delved into the world of the subconscious like The Persistence of Memory have catapulted him to the top of the surrealist movement.

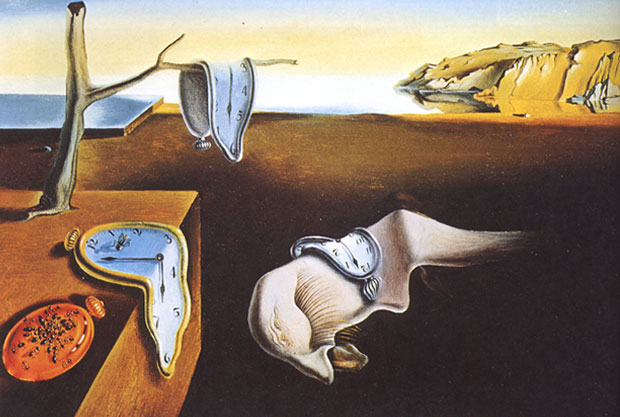

Salvadore Dali, The Persistence of Memory, 1931

Painted in 1931, and one of Dalí’s most famous works, the strange landscape is filled with melting pocket watches. Perhaps it alludes to the concept that time is not rigid. The iconic work is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

The painting that introduced me to Dalí when I was an adolescent, wandering around The National Gallery of Art in my home town, Washington, D.C., is the monumental Last Supper. More formally, it is The Sacrament of the Last Supper.

That picture, along with Renoir’s Girl with a Watering Can and the room full of Claude Monet ’s Rouen Cathedrals populate memories of my childhood when my father would drive me to The Mall in downtown D.C. and I would take my time perusing many of the Smithsonian buildings. That was certainly a different age, when nobody was fearful of kidnapping!

The Sacrament of the Last Supper, completed in 1955, is immense. I could feel that it had religious meaning and I was mesmerized by how beautifully each person was rendered. I was transfixed by the being that hovered above all the other figures. It seemed otherworldly. I didn’t know, at the age of about ten, that the central figure was Christ and he was surrounded by his 12 apostles. I would also not know that Dalí was experimenting with what he would call “mystical realism” by the time he made this work of art in the post World War II era.

Ironically, I have come to learn that the background of the scene’s setting is a landscape of Dalí’s Catalonia and that he also included such a landscape in The Persistence of Memory painting.

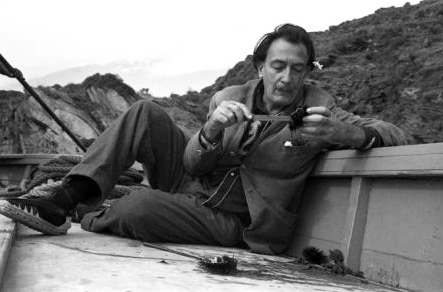

Salvador Dali eating sea urchin

Pursuing and eating “perfect creation”

My own persistence of memory, from beholding the Last Supper painting, to now craning my neck to take in the bronze rhinoceros underscores how the surreal mind of Dalí conjures up many different meanings for everything he ever created.

The greenish bronze sculpture contains another unusual element — two, in fact. One is by the right foot of the rhino, and the other is atop its back. These odd, bumpy balls perplexed me until I discovered that Dalí had a penchant for the sea urchin.

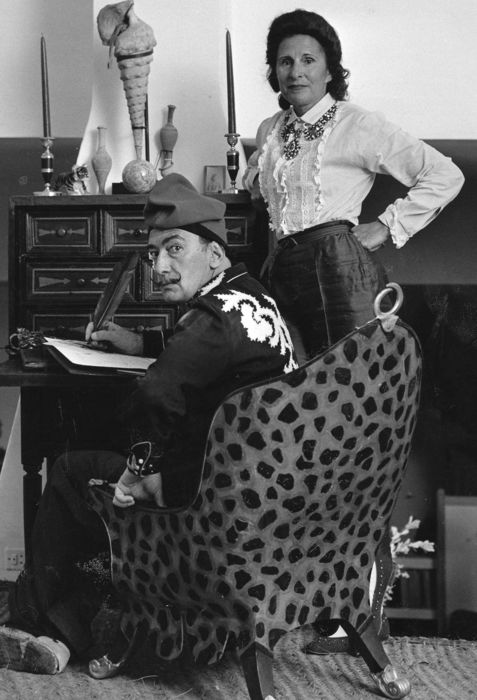

Salvador and Gala

In his world, it was a symbol of a perfect creation. There is even a legend, where according to Dalí, if an artist eats 36 sea urchins a day or two before the full moon and then takes a long siesta, an epiphany will occur as the artist sits before a blank canvas until it is too dark to see. This bizarre ritual will lead to a perfect work of art. Apparently it worked for him.

In 1922, Dalí moved into the Students’ Residence to study at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. When he left the academy, shortly before his exams, he was already a skilled draftsman. That same year he made his first visit to Paris, where he met Pablo Picasso, who had heard about Dalí from a fellow Catalan, Joan Miró. Over the coming years, Dalí would make a number of works strongly influenced by these two men.

In 1929, Dalí collaborated with surrealist film director Luis Buñuel on the short film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog). In August of that year, Dalí met Gala, who was married to surrealist poet Paul Éluard at the time. Destiny intervened. The Russian immigrant, born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova (and ten years his senior) eventually became Dalí’s wife and his primary muse.

A master of symbolism and visual pun

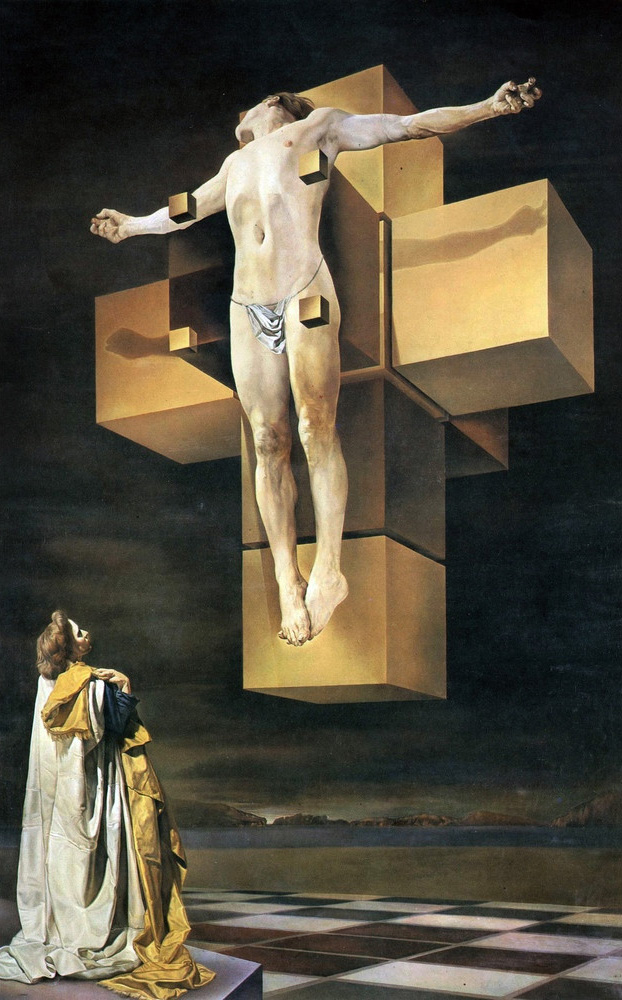

Also in 1929, Dalí had important professional exhibitions and officially joined the Surrealist group in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris. The Surrealists hailed what Dalí called his paranoiac-critical method of accessing the subconscious for greater artistic creativity. His keen interest in natural science and mathematics led to a fascination of DNA and the tesseract (a four-dimensional cube). This unfolding of a hypercube was featured in the painting Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus).

Salvador Dali, Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), 1929

Dalí was influenced by many styles of art, ranging from the most academically classic, to the most cutting-edge avant-garde. He used both classical and modernist techniques, sometimes in separate works, and sometimes combined. Exhibitions of his works in Barcelona attracted much attention and a mixture of praise and puzzled debate from critics.

Another attention-getter to go along with his theatrical behavior —Dalí grew a flamboyant moustache — influenced by 17th-century Spanish master painter Diego Velázquez. This moustache became an iconic trademark of his appearance for the rest of his life.

Late in his career Dalí explored many unusual or novel media and processes, incorporating optical illusions, negative space, visual puns and trompe l’œil visual effects. He also experimented with pointillism, enlarged half-tone dot grids (a technique which Roy Lichtenstein would later use). Young artists such as Andy Warhol proclaimed him an important influence on pop art.

If we survey Dalí’s entire oeuvre, we find the answer to the title of the “Rhinoceros Dressed in Lace” — like the visual pun, the title is a play on words — the delicate lace and impenetrable armor being exact opposites.

For those curious to see the rhino and the dozen or so other gigantic Dalí sculptures in Marbella, but you are not headed to the Costa del Sol anytime soon, you could visit the Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Here you can see the new AI version of the prophetic man who was so imbued with a sense of his own eternal significance, he said, “If someday I may die, although it is unlikely, I hope that the people in the cafes will say, ‘Dalí has died, but not entirely’ ”.

About the Author:

Taba Dale lives in Scottsdale, Arizona and County Clare, Ireland in the summer.

She has been an art dealer for almost 40 years and takes every opportunity to travel and enjoy art.